New Ark United Church of Christ,

Newark, DE

April 20, 2014 – Easter Sunday

He had been a

quadriplegic for most of his life, but that didn’t stop Dan Gottlieb from

realizing one of his lifelong dreams: to

be a stand-up comic. He had also wanted

to be a world healer, but in truth, both these ambitions could be one and the

same.

Dan had heard from a

friend that there was a comedy club in Philly that held month-long intensive

seminars for novices that they might hone their skill. So he began to make some inquiries. Was the comedy club wheelchair

accessible? Yes, it was. Was the stage accessible as well? Yes, it was.

He was told to prepare a routine ahead of time.

Dan was anxious as well

as excited. He’d probably be the oldest

one there, not to mention the only one in a wheelchair. He was also still concerned about the logistics

of it all. Would he be able to navigate

his wheelchair to the stage without attracting too much attention? How would he look on stage? Funny thing was, he wasn’t worried about

whether or not he would be funny.

When it was his turn, he

started down the aisle for the stage.

The lights might have been low where the audience was, and it’s not easy

to see everything on which the wheels might get caught. There was a lip at the end of the aisle. The wheelchair pitched forward and Dan with

it. His head landed on the concrete

floor, reinjuring his spinal cord. He

lost the use of his left hand, his dominant one, the one he used to feed

himself, drink from a cup, get around in his van, and a whole host of other

needful, vital things.

Dan woke up to

excruciating pain in both arms. He had a

brain clot and an acute concussion. At

first, he wasn’t able to speak. He

became septic and suffered through a brutal infection. He almost died. After a few days, having grasped the extent

of his injuries and worn out from the severity of the pain, he not only thought

but said to those around him, “That’s it.

I’m done.”

He was tired. He’d lived a full life. Dan had no desire to go through the months of

rehab it would take just so he could go home.

He’d already had a lifetime of adversity and not only survived but lived

a life fully alive, helping countless others, having had many adventures. It was enough. No more.

Not long after this

realization, Dan was looking out the window of his hospital room on a very gray

day. Nothing much to look at out

there. Then he looked down at his dead

left arm, just lying there, lifeless. Nothing

could have prepared him for what happened next.

He began to think about all the people who loved him, really, truly,

deeply loved him. There were dozens of

them, maybe lots of dozens. Dan says

that he felt that love in his chest, a huge warm feeling that filled him up and

spilled out of him, overwhelmed him to the point of tears.

Then he began to think

about all the people he loved, his chest, his heart, this feeling expanding

with every breath. He writes, “…I felt

such groundedness, almost giddy with joy and gratitude. I felt my body almost

couldn’t contain all the love I was feeling.”

He then looked down at his dead, lifeless arm and he said out loud,

“It’s a fucking arm!” He laughed at

himself. It was only an arm. Compared to all the love that surrounded him,

it was only an arm.[i]

We experience

resurrection in our bodies. We’re

constantly going back and forth about the bodily resurrection of Jesus, a

mystery that can’t possibly be solved.

We need to let go of that. The

resurrection was never intended to be an intellectual debate. All of the resurrection stories are

incarnational, in the flesh. Thomas

wouldn’t believe until he put his hand in Jesus’ side. The disciples ate a breakfast of cooked fish

with a resurrected Jesus. Jesus broke

bread with two friends on the road to Emmaus.

Mary heard her name and tried to reach for Jesus. To them, these weren’t visions or an

experience of the mind. Even the apostle

Paul, who didn’t know Jesus in the flesh, got knocked on his you-know-what,

heard a voice speaking to him, and temporarily lost his eyesight. The resurrection is a bodily experience.

Heather Abbott is

planning to attend the Boston Marathon next week, perhaps wearing her favorite

pair of 4-inch heels. What is

extraordinary about her plans is that she lost her left leg below the knee in

one of the explosions at the finish line of last year’s marathon. Even more so, only hours after being released

from a lengthy hospital stay, last year Heather threw out the first pitch at a

Red Sox game as she leaned on crutches.

After a grueling year of physical therapy and having to not only accept

but embrace her life as it is, she is now an example of resilience to others,

speaking to students, caregivers, and college graduates. To a room full of pharmacology students she

was able to joke, saying, “Right now I have six legs.” Resurrection is a bodily experience.

Like the stories of the

disciples, resurrection is also grounded in the experience of community, when a

body of people comes to life again. The

Sikhs of Oak Creek, Wisconsin still worship in the same temple or gurdwara

where six of their members were shot a year and a half ago. In Port-au-Prince, Haiti, though 150,000

continue to live in temporary shelters, 1,400 students attend a newly-constructed

secondary school called Artists for Justice and Peace School. Newtown, CT residents voted to demolish SandyHook Elementary School and to build a new school building at the same

site. Habitat for Humanity has been able

to repair 12,000 Filipino homes, with a commitment to build 30,000 super

typhoon and earthquake resistant homes.

Resurrection stories like

these and more may not always make network news, but it doesn’t have to stop us

from telling the good news out of bad news that happens every day, both around

the world and in our very own backyard.

In the church profile

that was shared with me was the story of how this church came to adopt its safe

conduct policy, a resurrection moment if ever there was one. A convicted sex-offender and his guardian

(for lack of a better word) approached the church to ask if they could worship

here. What was not known was that there

several people in this church who had suffered and recovered from sexual

abuse. One after another came forward,

in vulnerable honesty, seeking for all to be safe as well as being

compassionate and justice-minded. It

took time, for all to be heard, for all to be held in covenant. The one seeking safe haven moved on, but what

a gift he brought to the New Ark—the opportunity to truly be a safe place for

each other, in your bodies, in this body of Christ.

Clarence Jordan, the

founder of Koinonia Farm in Americus, GA, wrote: “The crowning evidence that

Jesus was alive was not a vacant grave, but a spirit-filled fellowship. Not a

rolled-away stone, but a carried-away church.”

It’s all about the body and how we incarnate, make flesh the

resurrection in our flesh, in our lives and in our life together. How have you experienced new life in your own

body? Is the New Ark ready to be carried

away with new possibilities, to renew this Spirit-filled fellowship?

The incarnation is the

resurrection, God alive again in our flesh, made visible in the way we live our

lives and in our life together. Thanks

be to God! Hallelujah!

|

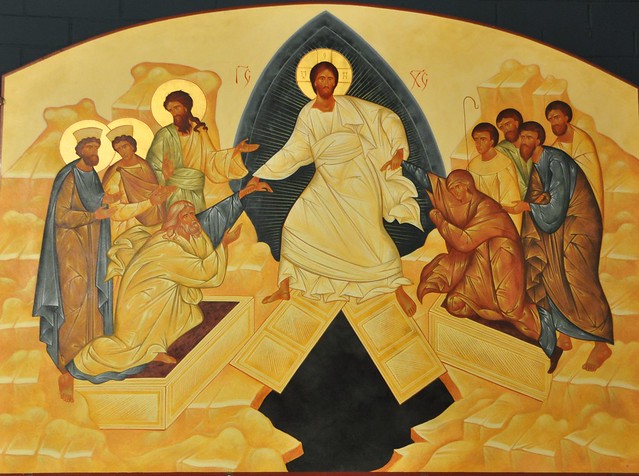

| After his resurrection, a rather burly Jesus raises Adam and Eve from their graves, thus raising all of humanity with him. |

[i]

Dan Gottlieb, The Wisdom We’re Born With:

Restoring Our Faith in Ourselves.

New York: Sterling Ethos, 2014.

pp. 62 – 67.