Matthew 21: 1-11

New Ark United Church of Christ,

Newark, DE

April 13, 2014

| ||

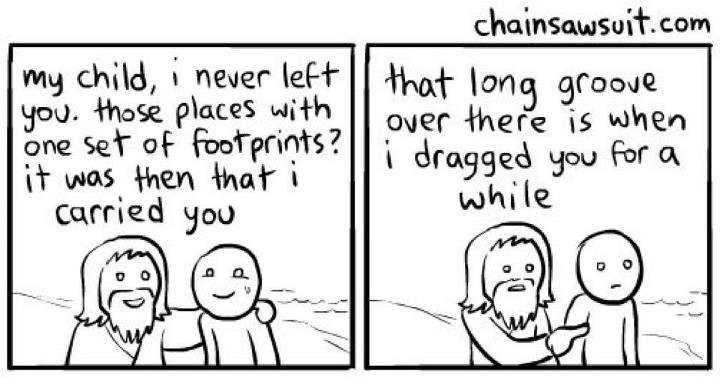

| He Qi. (China/USA) The triumphal entry ©2013 All rights reserved. |

Jesus and Satan have a discussion as to who is the better

programmer. This goes on for a few hours until they come to an agreement to

hold a contest, with God as the judge.

They sit themselves at their computers and begin. They type

furiously, lines of code streaming up the screen, for several hours

straight. Seconds before the end of the competition, a bolt of lightning

strikes, taking out the electricity. Moments later, the power is restored,

and God announces that the contest is over.

God asks Satan to show what he has come up with. Satan is

visibly upset, and cries, "I have nothing. I lost it all when the power

went out."

"Very well, then," says God, "let us see if

Jesus fared any better."

Jesus enters a command, and the screen comes to life in

vivid display, the voices of an angelic choir pour forth from the speakers.

Satan is astonished.

He stutters, "B-b-but how? I lost everything, yet

Jesus' program is intact. How did he do it?"

God smiles all-knowingly, "Jesus saves."

A

while ago I said that the church saved my life, but that was a story for

another time. I’d like to share that

story with you today.

I’ve

gone to church since I was an infant.

One of my first memories of church is the smell of the church office, of

the mimeograph machine, Scotch tape, sharpened pencils, all enriched by the

heat from steam radiators. Another early

memory is a print of a Sunday School picture, of Jesus’ entry into Jerusalem on

Palm Sunday, the crowd waving its palms while Jesus rode on a donkey. This framed print hung on my bedroom wall,

across from my bed.

Every

night, after my parents had tucked me in, I would look at that picture and

imagine God sitting on the edge of my bed.

We would talk about the day and what had happened. I then would say ‘goodnight’ to God and ask

Jesus to come in. Jesus would then sit

on the edge of my bed and we would have a similar conversation. But my bedtime talks with the divine ended

there because the only concept I had for the Spirit at that time was the Holy

Ghost, and I was scared of ghosts.

I

never doubted that there was a God. I

believed with my whole heart that God loved me, cared for me, would always be

there for me. That is, until my family

and how I experienced the world fell apart.

The

summer before sixth grade we moved to another town, from a small house of about

800 sq. feet to a new house of about twice that size, what I didn’t know then

was a last-ditch effort by my parents to save their marriage. New school, new people, new town. We had also started attending a different

church the year before.

The

next year, all the body changes kicked into high gear, along with my

emotions. That fall, when I was twelve,

my father left the house and my mother told me they were getting a

divorce. In two years the divorce was

final, my father remarried and moved to North Carolina. My mother’s boyfriend moved in. I came to the rude awakening that my father

had been an alcoholic and had been asked to leave my childhood,

awesome-smelling church as its Christian Ed. minister. And I started my freshman year in high

school, along with a killer case of acne.

It was a perfect adolescent storm.

Like most acts of nature,

and steeped in my childhood faith, I was convinced God was behind it all. I was angry and hurt. I cried myself to sleep most nights, feeling

as though God had abandoned me. I even

had thoughts of suicide. I just couldn’t

see my way out.

I don’t know what date it

was, but it was the morning of a school day.

I dreamed that I was watching a scene play out before me, of a group

people seated around a table in an abandoned shack. I could hear bombs and artillery exploding

outside, people screaming, dying. It was

a civil war, tearing apart a country.

The people gathered about the table were part of an underground

resistance: citizens from both sides of the conflict who wanted to end the

violence. There were maps on the table,

and they were making plans.

Suddenly there was a

knock at the door. The leader opened the

door, and there stood Jesus as I would imagine him—right from that print that

had hung on my bedroom wall—but the leader didn’t recognize him. “May I help you?” he asked rather

innocently. Jesus said that he came to

help them. The leader thanked him,

grateful for another pair of hands, another brain to wrap around the

problem. Space was made for Jesus around

the table, and the discussion began again.

Just then a woman’s

scream was heard right outside the door.

Everyone rushed out to see who it is.

It was one of their own, and she’d been stabbed in the back. Jesus reassured everyone that she would be

alright, picked her up, and brought her inside.

After some time passed, the wound disappeared from the woman and

appeared in Jesus’ flesh. In another

hour, both were healed and restored. The

entire group witnessed this, and they were confused. “How can this have happened? Who are you?”

Then I woke up.

Though it seems obvious

now, at that time I had no idea what this dream could mean. I had been going to youth group meetings at

my church and the pastor had offered to listen should I ever need to talk. We had spoken a couple of times, so I asked

him what the dream meant.

I was at war with

myself. There was a civil war inside me:

I was treating myself, my life, my relationship with God as though it was a

battlefield. I wanted to believe that

God was there for me, but I just couldn’t see it. Jesus would come and suffer with me and heal

me, but I had to recognize that he was there working in my life.

From that point on everything

changed. Actually, nothing changed. I did.

I began to see that there was a whole community of people who cared for

me and loved me and recognized spiritual gifts in me that I didn’t. They wore their faith on their shirt sleeves

and choir robes and t-shirts. They spoke

of their faith in their prayers on Sunday mornings, leading the congregation in

prayer but using first-person singular, their relationship with God vulnerable

for all to see. In the story of Jesus

they saw themselves, all the way to the cross and into Easter. Because of church, I began to see myself in

that story too, and through that story my life was saved.

When the crowds welcomed

Jesus as he entered Jerusalem, they cried out, “Hosanna to the Son of David!” When the people shouted out “Hosanna”, it

wasn’t just a cheer of joy but a plea for rescue: Hosanna means ‘save us’. On the other side of town, through the

western gate, most likely a legion of Roman soldiers were entering Jerusalem,

as they usually did during Jewish holy days to quell any ideas of uprising

against the occupation. When the Jews

cried out, “Save us”, they saw Jesus as the messiah who would lead an army

against the Romans and force them out of Israel.

The words “save us”,

“saved”, “salvation”, “sin”, “rescue” have fallen out of favor in the

post-modern, progressive church, having been co-opted by more evangelical and

fundamental forms of faith. Even more

so, most days we don’t like to admit that we need rescue or salvation, let

alone these may have lost their meaning for us.

We don’t have a theology

of liberation in the predominantly white, middle-class church. The civil rights movement, those living under

oppressive regimes such as Archbishop Oscar Romeo and the people of El

Salvador—they found meaning and purpose story of Moses leading the Israelites

to freedom. It is difficult for us to

comprehend what we need to be saved from when we live with privilege in a

dominant system.

Yet each week and in our

own devotional use of the Lord’s Prayer, we say “Lead us not into temptation

but deliver us from evil.” We know that we cannot be delivered safely

from the evils of this world. If it’s

one thing the daily news teaches us is that evil can come down on anyone,

anywhere, at any time.

The evil for which we

need deliverance, liberation, rescue, salvation is the evil within us, the evil

of which we are all capable, and the evil we participate in—systemic, cultural,

societal evil. We commit sins and we and

those around us suffer the consequences of them. When we admit we need saving, we acknowledge

that there is a power greater than ourselves that can restore us and restore

humankind to sanity. When we confess

that we need rescue, we recognize our place in the universe, as interdependent

and connected to one another. When we

accept that we cannot save ourselves, we can let go of the desire to control

the outcome and make more room for joy in our lives.

We believe that God is

still speaking. If we have difficulty

with words like “saved”, “salvation”, and “sin”, we limit God’s lexicon. As one member of my family put it, saved is

about giving or getting help at just the right time. And at the right time God sent Jesus to save

us—from ourselves.

How has the church, being

of the Body of Christ, saved your life?

Can you see yourself and this church in the salvation story? What are the ways of living that lead to

death that we continue to need to be saved from? How can we as a progressive church not only

embrace a theology of liberation but embody it in our ministry?

We live in a world that

indeed needs saving. But we cannot do

this saving work if we ourselves do not acknowledge our need for it as

well. Thanks be to God for liberation,

for rescue, for grace that saves us just at the right time. Just in time to be relieved of our fear,

forgiven of our sin, freed so that we might freely choose, that we might live and

serve in joy. Amen.

1 comment:

Amen! And blessings to you for sharing your story with us! <3

Post a Comment